The Fed's Lost Grip on Interest Rates

- Text size

As widely expected, the Fed finally ended its massive bond-purchasing program.

Now the market will turn its focus to interest rates.

Will the Fed raise rates next year? If so, what effects will that have?

The Fed is ultimately reactive, exerting little, if any, control in the long run. Low rates are here only as long as the Fed can manage them.

At that point, it is time to look out.

Here's what will cause us nightmares, and what we can do to avert a crisis in our investments…

Americans Tighten Their Belts… While Their Government Races Toward Disaster

The International Center for Monetary and Banking Studies recently published its 16th annual Geneva Report. It's authored by a group of senior economists and former senior central bankers.

The report highlights a sustained increase in (especially) government debt in the developed world, as well as in China. Any deleveraging in the last few years has been minor, mostly limited to the private sector.

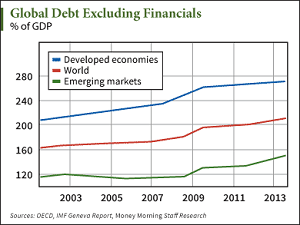

It goes on to caution the importance of low rates to stave off another crisis, while pointing out that, as the graph below shows, world debt has mushroomed from 160% of national income in 2001, to 200% in 2009, only to climb further to 215% last year.

As a group, the report's authors expect interest rates worldwide to remain low for a "very, very long time," so that all borrowers (governments, companies, and individuals) will remain solvent and keep paying the interest on their debts.

As a group, the report's authors expect interest rates worldwide to remain low for a "very, very long time," so that all borrowers (governments, companies, and individuals) will remain solvent and keep paying the interest on their debts.

So too does Ben Broadbent, deputy governor of the Bank of England, saying interest rates could remain "permanently" low.

All of this echoes what the Fed's been saying for years in order to reassure and stimulate the markets: there is no rush to raise rates.

None of this is really any surprise to us. But it's not quite that simple….

The Fed's Dangerous Catch-22

As we discussed recently, many expect the Fed to raise rates next year (more on this below), while Europe and Japan recently pushed their rates below zero to help fight off deflation.

Sweden's central bank, the Riksbank, recently cut its own key interest rate to 0% from 0.25%. Swedish central planners there think inflation is still too low, and want a monetary policy that's "even more expansionary" as they target 2% inflation.

In mid-October we heard noise from two regional Fed presidents, John Williams and James Bullard, countering expectations for the Fed to take its foot off the gas. First Williams of the San Francisco Federal Reserve said, "If we really get a sustained, disinflationary forecast … then I think moving back to additional asset purchases in a situation like that should be something we should seriously consider."

Next, the St. Louis Fed's Bullard said it might make sense for the Fed to delay ending its bond-purchase program to halt lowered inflation expectations, and that, "We could react with more QE if we wanted to."

Much more intriguing, however, is research by Citigroup on just how much stimulus the markets need.

Their report estimates that zero stimulus would lead to a 10% drop in equities every quarter, and that central banks need to inject some $200 billion quarterly just to sustain market levels.

Strategists at Bank of America Merrill Lynch figure that another 10% drop in U.S. stocks could lead to a fresh new round of stimulus, QE4.

With all these conflicting signals, what's an investor to expect, really?

Well, now that the end of bond-buying is official, let's look at the Fed's next nemesis: interest rates.

Look for Interest Rates to Do This

The CBO (Congressional Budget Office) estimates that, should interest rates return to normal levels by the end of this decade – just over five years from now – the country's annual debt payments will surge to over $840 billion annually, double current levels.

Precious little will be left over for useless government programs and vote buying.

My own view is we'll likely see rates rise next year, but even then only by token amounts. Expect increases in the 0.1% to 0.15% range, with the Fed taking its sweet time before ending the hikes, which are likely to top out in the 2% to 3% area only several years from now.

The Fed knows that the Treasury simply cannot afford anything more.

That approach will allow the Fed to save face, keeping its promise to raise rates, while having minimal impact on debt payments and lessening the risk of deflation.

What should concern investors is the serious and growing risk of a currency or bond crisis.

The Geneva Report points out that record debt and slowing growth form a "poisonous combination," potentially leading the global economy into yet another crisis.

Although we can't know exactly the point where just one more snowflake initiates the avalanche – to use Jim Rickards' analogy in The Death of Money – that point exists nonetheless.

And we're getting closer to it, not farther.

Ever-growing debt will trigger a bond crisis, with bondholders deciding "enough is enough" and dumping their bonds wholesale. It's a crisis of confidence that will devastate the bond market, causing yields to surge.

This is why, ultimately, the Fed doesn't control rates.

Newly issued bonds will then have to pay much higher interest to compete with prevailing yields. And that will crush the government's ability to keep up with servicing its debt payments.

I foresee two scenarios holding true through this.

Cash will lose purchasing power thanks to inflation, and real estate will see headwinds as higher interest rates make homes more costly and revenue properties less profitable. Real estate bought with little or no mortgage is clearly preferable.

Ultimately, gold and silver remain your top hard asset choices to counter the coming bond crisis.

Remember, the Fed will do its best to keep rates low. Which is exactly its quandary, since the runaway debt created by extended low rates will cause the next crisis.

Even the Fed isn't omnipotent. Market forces will teach them that lesson.

About the Author

Peter Krauth is the Resource Specialist for Money Map Press and has contributed some of the most popular and highly regarded investing articles on Money Morning. Peter is headquartered in resource-rich Canada, but he travels around the world to dig up the very best profit opportunity, whether it's in gold, silver, oil, coal, or even potash.

AJ adds: I frankly did not believe that the FED could end QE, or that the ending would be clean and permanent. I did not believe either that the banks would crash the gold price, but they did. The problem is that rather than solve the problem (too much government which lowers efficiency) the banks allow the govts to maintain involvement in the economies. The result is lower efficiency, reduced growth and lower living standards for the masses. The more the banks interfere with the markets, the more they hazard if they are wrong. And technological improvements can not compensate for the decreased efficiency caused by govt involvement.

No comments:

Post a Comment